THE SILENCE IN THE FOREST by Iain Sinclair

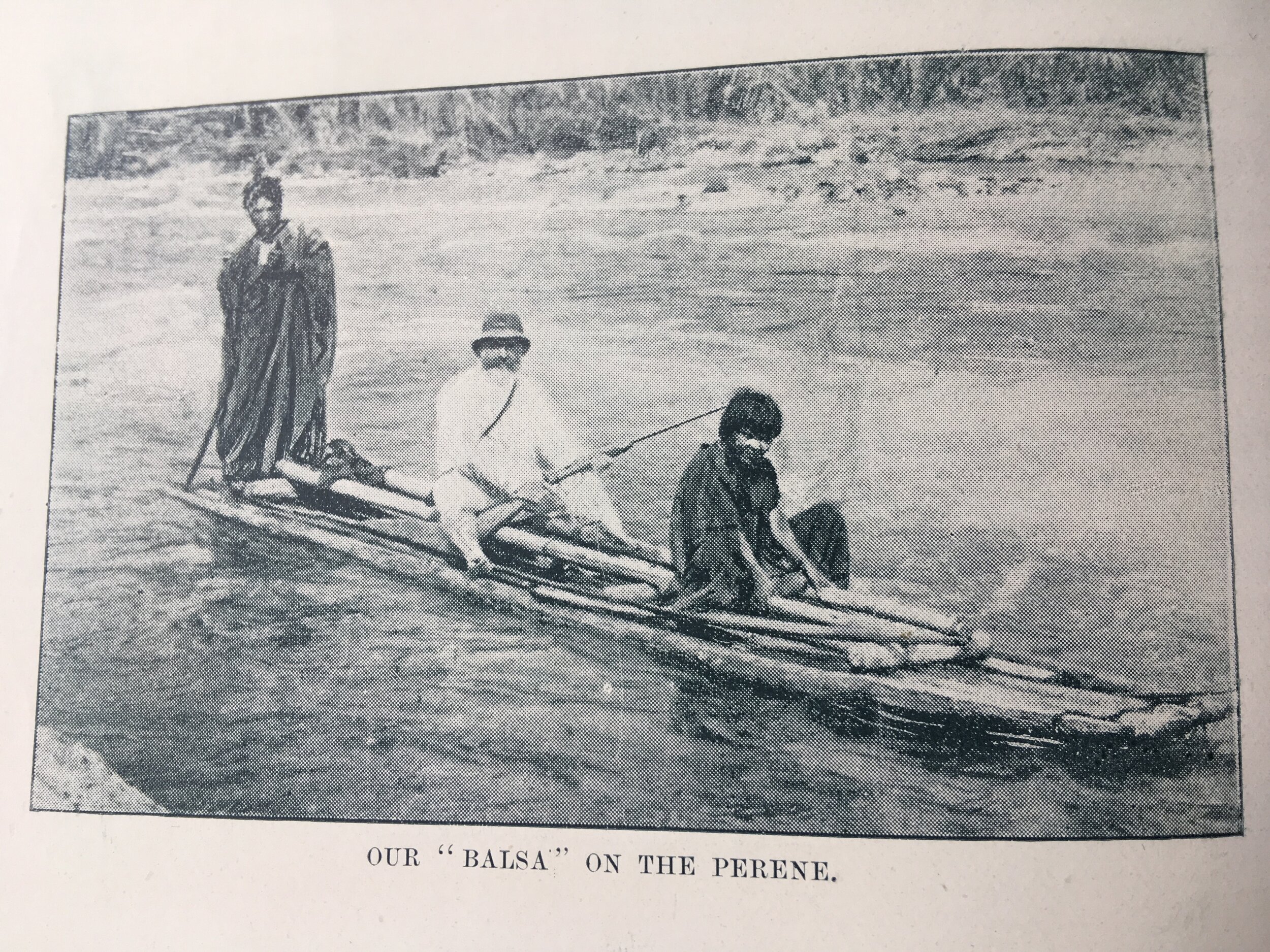

My great-grandfather, Arthur Sinclair, guided – in his view – by a pair of duplicitous and drunken priests, was stumbling and slithering down the old Ashaninka salt route, a future trade highway, towards an encounter with the indigenous chief who would give the command for the construction of balsa rafts to carry the invaders along the Rio Perené to impassable rapids. And the whirlpool of dead ancestors. The commissioned surveyors, former planters from Ceylon, were done, ready to lie down where they stood, weapons across their laps, when they chanced on a great secret. It was hidden in plain sight a short distance from the settlements of Metraro and Mariscal Cáceres, linked villages that would, in a few years, come to be dominated by Seventh-day Adventists offering school, chapel and medical care. All with the tacit approval of the Peruvian Corporation of London, corporate predators who established the coffee estates on which the villagers were obliged to labour.

by Arthur Sinclair, from his book, In Tropical Lands, Recent Travels to the Sources of the Amazon

But the road was a villainous rut at a gradient of about one in three, a width of about eighteen inches, and knee-deep in something like liquid glue, Sinclair wrote, in a book published in 1895. Before we had gone five miles one-half the cavalcade had come to grief, and it was some weeks ere we saw our pack mules again; indeed, I believe some of them lie there still. We soon found out that the padres knew as little about the path as we did ourselves, and the upshot was we were benighted.

Shortly after six o’clock we were overtaken by inky darkness, yet we plodded on, bespattered with mud, tired, bitten, and blistered by various insects. Whole boxes of matches were burned in enabling us to scramble over logs or avoid the deepest swamps. At last there was a slight opening in the forest, and the ruins of an old thatched shed were discovered, with one end of a broken beam still resting upon an upright post, sufficient to shelter us from the heavy dews. It turned out to be the tomb of some old Inca chief whose bones have lain quiet for over 300 years, and there on the damp earth, we lay down beside them, just as we were. Our dinner consisted of a few sardines, which we ate, I shall not say greedily, for I felt tired and sulky, keeping a suspicious eye upon the Jesuit priests.

The trail guides, Franciscan not Jesuit, were not deceiving this trio of white adventurers, hiding behind beards, dispatched by the Peruvian Corporation of London. Sinclair’s party was being led down an ancient desire line, from the Mountain of Salt to the living, surging, serpentine river, by way of the burial place of a godlike warrior, a splinter of origin. Reflection of Father Sun. The priests were initiating these pale outsiders, nudging them forward with hints and selective misinformation, through an unformulated chart of the psychic energies that protected this place and kept it free from the depredations of alien capital. 1891 was a fateful year, with three major expeditions - military, engineering and commercial - all hell-bent on pioneering routes for exploitation of a savage and enduringly lovely Eden. The garden from which Europeans had been expelled.

We were told, by the way, that the bones we were handling were the bones of Atahualpa, so treacherously murdered by Pizarro.

A fantastic fable the priests concoct to entrap the credulous colonists with their moleskin journals and Kodak cameras. But in lisping such lies and alternative histories, the fathers were also demonstrating respect for tactics employed by indigenous people under interrogation: agree reluctantly, after sharing food and exchanging gifts, to tell strangers whatever they want to know. Then contradict yourself, offer multiple versions. And deny all knowledge of the original conversation when you meet on another day.

Atahualpa, the ‘last Inca Emperor’, was strangled with the infamous garrotte on 26 July 1533, before his clothes and raw strips torn from his skin were burned. A merciful amendment to the original verdict: barbecuing at the stake. This sinister ritual was enacted many miles from Metraro. It was said that the Inca offered to fill a large room with gold, in order to ransom his life. After the mock trial, more of a pre-ordained ritual than a measured evaluation of guilt, an attendant friar, Vincente de Valverde, pressed his breviary into the affronted hands of the condemned man. Atahualpa was baptized into the Catholic faith and marked with the name Francisco - in honour of his conqueror, the Spanish illiterate suckled by sows, the notorious butcher of worlds, Francisco Pizarro.

Gold was intoxication. So fill the holds of creaking cargo fleets and the expectant watchtowers of Seville. Cast another saint for another cathedral. Túpac Amaru, hereditary Inca rebel, was beheaded in Cuzco’s Plaza de Armas, forty years after the death of Atahualpa. A persistent Andean myth claimed that the buried head would reconstitute itself, and grow another body, in order to initiate a golden age and a second Inca empire. Arthur Sinclair soon discovered that the site where he had slept was dedicated to a different Atahualpa, the charismatic Juan Santos, a highlander who adopted the title of the Inca emperor when he led a very effective revolt against the Spaniards in the 1740s.

I arrived in Mariscal Cáceres with my daughter, Farne, on 9 July 2019. We were determined, if it were at all possible, to persuade one of the villagers to guide us to the burial place of Juan Santos Atahualpa. The point of connection with my great-grandfather’s narrative. The Ashaninka we had previously interviewed told so many contradictory versions of the same story: the shrine or hole or cavern belonged with the legends of childhood. A song of their grandmothers. With truths it was forbidden to reveal. With the land. Their land. Juan Santos Atahualpa had emerged from some generative source like a black nuclear sun: a light so brilliant that eyes hidden behind shielding hands could witness finger bones dissolving. The great chief, their undead and unsleeping commander, was said to be a spectre of whiteness: Juan Santos had travelled in foreign climes. And walked home across the obedient waves. We were bouncing and shuddering up the mountain road that force of necessity had evolved from the original 1891 incursions of the military engineers. My great-grandfather was not impressed.

I have in other countries travelled in tracks traced and made by elephants, and had reason to admire their gradients and marvel at the topographical knowledge displayed, but anything so perfectly idiotic as this atrocious trail I had never before been doomed to follow so far. It was a relief to leave it and cut our own way through the jungle.

A few miles out of Santa Ana, where rainy season landslides had turned the river into a ditch of red, mud-plastered rocks, we had to cede a little of our headlong velocity to avoid jolting over a ragged man sleeping in the middle of the road like a performance art traffic-calming device. He was known. He would stagger to his feet in a few hours and make his unsteady way back to the nearest hamlet, where he would find a little food and drink, enough to sustain him for another day. He was part of the intricate clockwork of the territory.

The road had as many twists and eddies as the river. As soon as we started to climb, the brutal gradient committed itself to preparing us for Mariscal Cáceres. Tumbledown shacks made from scavenged planks owed their survival to the capitalised electoral slogans painted on their sides: (EL NEGRO) VENEGAS, EXPERIENCA y CAPACIDAD. Around a hairpin bend, beyond the point where an old woman had a stall serving some lethal fermented drink, was a big blue sign with a schematic picture of a stooped pedestrian, propped up by a pilgrim’s staff. He appeared to be skipping across a torrent. CAVERNA JUAN SANTOS ATAHUALPA. 11.6 km. And another skeletal silhouette at the mouth of a cave: CAVERNA METRARO 9.9 km. The implication being that the cave of Juan Santos Atahualpa is 1.7 km beyond the village we are approaching. But when we return down this same road that blue sign has vanished.

The old lady we left behind in the smoky twilight of the village settlement beside the Perené, told us, as we blinked and rubbed our eyes, that the cave – she had never been there herself – was once filled with weapons used in the war against the colonists. In time, the Spaniards found and stole them. Now, dusty and shaken, when we arrive at Mariscal Cáceres, the same old lady, Bertha, is there ahead of us, helping to prepare the fish. She said that the body of Juan Santos had been laid to rest on a bed of gold. Gold recovered from the Spaniards. And gold, heaped up, always multiplies like a harvest of desire. Juan Santos Atahualpa guarded it. One of the village elders said that the shrine was just a few hundred yards from where we were sitting and talking. It would take us ten minutes to walk there. After the meal, several hours in preparation, was done and the exchanges made, the chief came to see us, a tame green parrot perched on his finger. The parrot whispered something in his patron’s ear. The chief said that he would lead us to the cave. But it was too far to walk, before light failed, so we would have to return to our car and follow the guides on their motorbike.

The official biker was a slight, stringy man, with a bandit beard. And a baseball cap with an italicised, lowercase slogan: dope. We were too quick to typecast this character as a trafficker, a coca mule who knew the best paths between the Salt Mountain and the Gran Pajonál. But the village chief, sitting behind the biker, bareheaded, was in charge. They took us for a mazy ride, twenty minutes, forty minutes, past plantations of blackened bananas, over treacle tracks that were reverting to streams. Without warning, they stopped. And beckoned for us to follow.

The man in the dope cap used his machete to cut a bamboo walking pole for my daughter. The path through the jungle was steep. We imagined the sound of a distant torrent. The chief, in his flip-flops, was moving fast. We gripped the curtain of vines under the dripping rock. The cliff crumbled as we rubbed against it, trying to stay on the provisional track. When our guide was gone, we hooked ourselves to saplings, right where we were, catching our breaths, but scarcely breathing, as the biker explained how the chief need to confirm that the path to the cave of Juan Santos Atahualpa was navigable. ‘It’s not so very far, twenty minutes more.’

Heavy sugars of excitement, not fear, are absorbed in the luxuriance of the all-enveloping trees. Sap informs our sweat. If we can no longer hear the sound of the chief pushing branches aside, there is no reason to expect his return. ‘It is not the presence of unfriendly natives that wears one down,’ Michael Taussig wrote in Shamanism, Colonialism and the Wild Man (A Study in Terror and Healing). ‘It is the presence of their absence, their presence in their absence.’ Place, when breath is swallowed and held, dissolves the distinction between myth and documentation. ‘People buried in an underground of time in the lowland jungles,’ Taussig claims, ‘are endowed with magical force to flower into the present.’

All forward momentum, towards the cave, and the teasing prospect of gold, is stalled. Warm, saturated air flows through us. We steady ourselves against strands of slippery vegetation. Martin Macinnes in Infinite Ground, a novel of disappearance and diminishing volition, catches the peculiar inertia that comes with being in the right place for the wrong story. ‘For the moment he didn’t seem specifically located, just general in the sounds of the birds calling, water dropping, twigs breaking and the branches falling.’

It was a process of folding into the baffle of silence. We became aware, father, daughter, great-grandfather, of a shared identity. Resistance and dissolution of conditioned reflexes. And the mute presence of the biker, the man in the dope cap, our familiar and trickster. And his special relationship with the jungle and the path; how he was permitted to pass through, only so long as he stayed on sanctioned routes, stayed within his agreed role. But now he was separated from the chief, the man who had bounded so rapidly beyond sight and sound. There was only the smothering foliage and a projected sympathy between trees, birds, stones, streams and intruders. The fronds of the giant ferns were slatted blinds filtering a lovely distillation of sunlight – before, on the stroke of 6 o’clock, it withdraws completely. We were no longer waiting for anything or anybody. There was no conversation. ‘He was the deep sounds in the forest that had no explanation, the shadow at the edge of one’s vision,’ Joe Jackson wrote in The Thief at the End of the World. He was describing the fever dream of a renegade English plant-hunter and rubber pirate, Henry Wickham. Broken in health, attended by vultures, Wickham was nursed by neighbours who knew that he was doomed when he said that he had seen the curupira, ‘the little pale man of the forest’. The harbinger of mortality emerging from a tangle of roots. ‘The souls of those who died at the hands of the curupira wandered forever in the forest. Survivors left part of themselves beneath the canopy and were never the same.’

What had my great-grandfather, processed by two drunken priests down this same track, left behind? What would we leave, beyond some lame attempt to describe the magic of the place in which we found ourselves? I thought, in a delirious fugue of remembering, of trying to report with accuracy a sudden flashback to a golden November morning in Victoria Park in London. The sun rising over the mist on the lake, a natural miracle too real to record. That place and this place and my identity lost between the two. There was a man on the long avenue of the park, gripping a pilgrim’s stave in his right hand, elegant in a long black coat, like a jaded but sensuous architect in a French film, walking steadily backwards. As if to confuse fate and win back a few hours. I watched his confident progress. What would happen, I wondered, when he reached the railings? He swerved slightly, made an adjustment, and passed on, before dropping out of sight. He could have been a world travelling sadhu. Or a tenured Hackney veteran proud of his calibrated eccentricity. The famous backwards walker.

Memory does not help. We might never move again. The chief would not return and our biker guide was not permitted to lead us out of the jungle without him. We could not invent the sound of the waterfall. Or the oracular echoes in the aperture of the secret cave. There would be few better moments in our lives. No more profound engagement with the concept of place. Slowly, breath by breath, we gave ourselves up to a pre-linguistic where. And to the stately dance of malicious shadows. ‘The evidence of his family line and all its members,’ Martin Macinnes wrote, ‘stained in the leaves.’ Arthur Sinclair, out of his knowledge, on the cusp of fever and hallucination, fated to bring back a favourable report, did come out of the rainforest, after that terrible night, waking on a pillow of bones. He came out of the strangling confusion of the blasphemous jungle. Into the visions my daughter had chosen to investigate.

I shall never forget that calm, bright Sunday afternoon when we looked out for the first time on the great interminable forest of the upper valleys of the Amazon. Right in front of us as we stood with our faces to the east were evergreen hills of various altitudes, all richly clad, and undulating down towards the great plains of Brazil. We were standing at a height of 4,600 feet, but, even in that clear atmosphere, could see but a comparatively short distance; still it showed better than any words can convey the extent and richness of this vast reserve, and the absurdity of the cry that the world is getting over-crowded. Why, we have only as yet been nibbling at the outside borders, and are now trying to peep over the walls of the great garden itself... The faint buzzing of bees, the subdued chirping of finely feathered birds, the flutter of brilliant butterflies, are the only commotion in the air, itself the perfection of summer temperature. What a glorious spot in which to form a quiet, comfortable home! Imagine this all the year round, every month seedtime and every month harvest. What crops of vegetables and fruit might not be produced in such a climate and such a soil! Had poor old Malthus only been permitted to look upon a country like this, so rich, and yet so tenantless, his pessimistic fears of the population outgrowing the means of sustenance would have quickly vanished.

What rapacious innocence! How seductive the report lying on the desk of the investors in Leadenhall Street. Already the gold of the rainforest was turning green and blood berries, soon to be harvested by indentured Ashaninka slaves, were ripening on high ground where the boundary fences of the Coffee Colony would be set. And barracks with barred windows constructed. And overseers hired. And books of memory published only to bring forth other books.

PHOTO CREDITS: IAIN SINCLAIR